When I was 8

This tropical place triggers memories of another tropical place

I’ve been thinking a lot about the first few years after my family moved to Singapore, when I was eight. Eight is how old Beanie is, and I am watching her adjust to a new school and new clime from the perspective of parent now. The experiences don’t parallel completely, but the similarities have brought me back to a time I haven’t thought about much in decades.

When we first moved to Singapore from California, we lived in a bare white two-storey, at the end of a row of terrace houses. The residences in this neighborhood were built in the 1960s for British Armed Forces personnel. Later, they became housing for expatriate instructors at the universities and international schools of Singapore, of which my dad was one. (For those of you familiar with Singapore, you’ll probably recognize I’m writing about Chip Bee Gardens. I looked our house up on Google Maps and it looks almost the same as when we lived there, nearly 40 years ago).

The house had no air-conditioning, and we were acclimated to mild SF Bay Area weather. I remember being hot all the time, and lying on a xi zi (Chinese woven mat) under a spinning black ceiling fan, trying to fall asleep in the heavy wet heat. Sometimes during the hottest afternoons, I would lie on the cool tiles of the living room floor, shifting my spot when my body heat made the tiles underneath me too warm to be useful.

Everything was strange. It felt like we had descended upon an alien land. Even the grass wasn’t the same as back home.

The environment and vegetation here in Costa Rica is very similar to Singapore. Bright red hibiscus flowers from the bush outside fall onto our car after heavy rains. I can find the same fruits from my childhood—starfruit, soursop, mangosteens, rambutans, papayas. In our Chip Bee backyard, we had a papaya tree and we harvested papayas fresh from the tree. I learned that I did not like papayas very much, however fresh they might be.

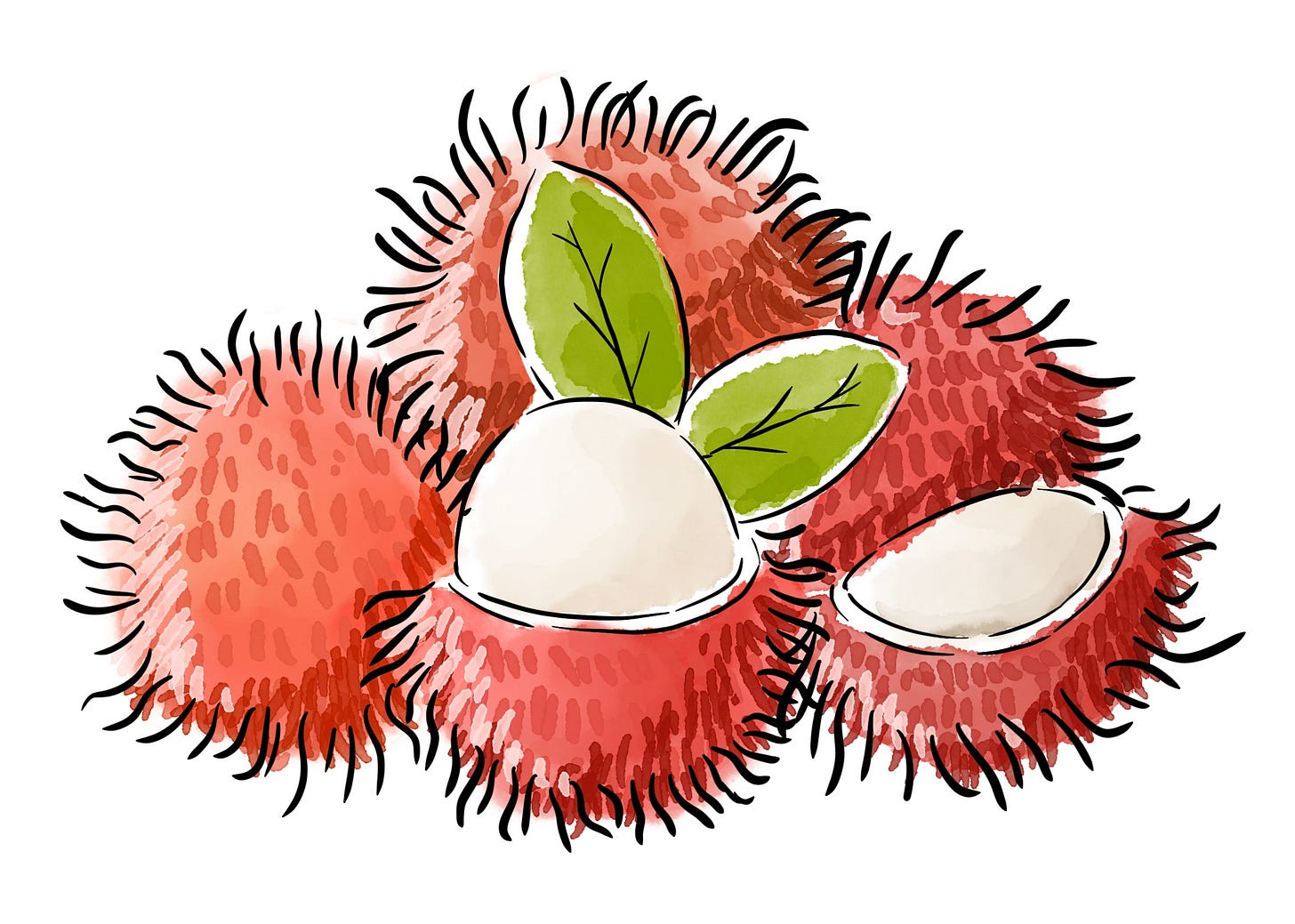

I found more success with rambutans, and was fascinated by their hairiness. What a crazy fruit that looks like it shouldn’t exist! (see also: durians) Apparently, the hairs help in pollination, since pollen can get hooked onto them and transported to female rambutan flowers.

I can’t look at a rambutan without thinking of a song we learned in primary school:

Rambutans, rambutans, red-o,

Rambutans, rambutans, sweet-o.

Rambutans, rambutans, red and sweet,

Rambutans, rambutans, good to eat.

It’s a banger of a song. I Googled and could not find mention of it anywhere, which honestly does not surprise me.

Less appealing than the fruit are the bugs. We’ve found a variety of bugs in their death throes here, including a cockroach that seemed to have expired but began scuttling as soon as I tried to pick it up with a paper towel (Reader, I shrieked.) Fortunately, the scale of bugginess is not anywhere near what we had in Chip Bee: I remember turning on the kitchen lights during the night and watching dozens of cockroaches scatter. I remember helping my mom pick weevils out of our rice bin. My mom remembers walking into the kitchen one day to face a two-foot-wide river of ants flowing down her kitchen wall. When she mentioned it to me this week, I remembered it too. I had shut that memory up tight in my mind, for good reason. If I were my mom, I probably would have demanded to move elsewhere that very day.

My most visceral memories come from the smells here that bring back, in a flash, specific images from my childhood. A prominent one is the smell of earth and wet asphalt after a torrential rain (the rain here is also familiar to me, sheets of it coming down in volumes that pelt the skin). That smell mix takes me instantly to early mornings during primary school, when I stood outside my house waiting for the school bus in the dark.

I was curious why my smell memories are so immediate, and often so emotional, so I looked it up: That smell evokes such profound remembrances—more so than the other senses—is likely due to the architecture of the brain. When we hear a sound, it goes through a circuitous route from the ear through other parts of the brain, before arriving at the auditory cortex. In contrast, a smell hits the smell-sensing neurons in the nose, goes straight to the olfactory bulb of the brain, and from there connects directly to the amygdala (the part of the brain that processes emotion) and the hippocampus (the part responsible for memory).

Smell is the most developed sense in children under 10 years old, and childhood is when one experiences most smells for the first time--so it's no surprise many smell memories are also childhood memories.

About two years after we moved to Chip Bee Gardens, we moved away to a flat, and from then on we only stayed in flats. We were no longer close to the ground, and we no longer dealt with the many creatures that came with earthbound territory. By that time, our family was settled into the rhythm of work and school, and Singapore didn’t feel foreign anymore. The flats we lived in didn’t have many ants or cockroaches, and though the air continued to be humid, there were layers upon layers of concrete and structure between us and nature. Oh, and we had air-conditioning in every bedroom. My interactions with my environment had changed.

That time in Chip Bee remains a short but distinct era, vivid in my mind from the novelty of being dropped into a strange and brilliantly colored land, with fruits that belonged in some kind of fairy tale and critters that were the stuff of nightmares.

Living in this house in Costa Rica is surfacing memories of that specific Chip Bee era, more than all my years in Singapore since then have ever done. So many small memories have unearthed themselves in the past few weeks, I’m surprised. They were rattling around in my brain this whole time.

It does make me wonder where Beanie will be decades from now, when the smell of warm rain on asphalt or the sight of butterflies dancing around a hibiscus bush brings her back to those days when she was eight, smashing coconuts with her new friends in a schoolyard in Costa Rica.

Pretty Good Things

Your Memory is like the Telephone Game

I think about these memory studies (below) every time my mind conjures up a treasured happy memory. Ever since I learned how fragile memories are, and how easily they can be rewritten when they are recalled, I’ve been a little afraid to consciously bring up good memories, lest they be corrupted. The human mind is so resilient and yet so vulnerable.

When Memories Are Remembered, They Can Be Rewritten

Your Memory is like the Telephone Game:

“A memory is not simply an image produced by time traveling back to the original event -- it can be an image that is somewhat distorted because of the prior times you remembered it,” said Donna Bridge, a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and lead author of the paper on the study recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience. “Your memory of an event can grow less precise even to the point of being totally false with each retrieval.”

Meaningless change is crucial for our lives

From Chris Guillebeau’s blogpost this week, I learned about Tehching Hsieh, an artist whose radical experiments in the 1970s and 80s included spending a year in a cage with no entertainment whatsoever—no reading material, nothing to write with, no television—and another year punching a time clock every hour, round the clock.

I’m not sure what to make of these excruciating experiments, other than to admire Hsieh for his superhuman commitment. Of the time clock piece, Hsieh once said:

“Meaningless change is crucial for our lives. We are obliged to pay attention and take care of details.”

Guillebeau’s takeaway from the time clock piece is that

Not all change is meaningless, of course, but a lot of it is. Every day we pass many, many hours that we’ll never think about again. Often we spend entire days, weeks, or even longer periods of time that disappear into a void.

We can try to fill those days with meaning, changing our activities, reordering our priorities, and so on. Or perhaps, as Hsieh demonstrated through his fascinating, brutally difficult project—we just need to pay closer attention.