Educator series #5. University lecturer and unschooler

Hello, friends.

Allie’s daughter, L, goes to nature school with Beanie. Through our chats, I’d gotten glimpses into Allie’s educational philosophy, and I knew it was carefully considered and unconventional.

Allie has always excelled academically at school, she holds a PhD, and she teaches architecture at a university. She is, by traditional metrics, a school system success story. Her old friends are surprised when they learn she homeschools her own children, but she has come to her philosophy after many years of learning and experience, as a mother and an educator.

In addition to L, she has two teen sons, H and Z, who currently homeschool. The family moved here to Vancouver from Australia eight years ago so oldest son H, who is neurodivergent, could attend the Eaton Arrowsmith Center for Neuroeducation.

H tried seven schools between kindergarten and Grade Three, both in Australia and Canada. Being on the autism spectrum, socializing was challenging. Some teachers treated him as if he was stupid because he was autistic, and school often made him uncomfortable, so he’d behave “weirdly,” crawling on the floor or hiding under a desk.

Not finding good school options, Allie began homeschooling H with a curriculum book she bought at Costco, sitting next to him while he worked through exercises. H was bored and lonely, but Allie did realize while watching him go through his Grade Three math book that he was not “stupid” at all.

“He would just fill in the page and turn it, fill it in, turn it, like nothing was challenging,” Allie says.

With H feeling lonely at home and Allie busy with work and study, they decided to try one more school, Madrona, for “kids exactly like him who are bright but quirky.” It went relatively well. H stayed at Madrona until Covid lockdown, when suddenly the whole family was at home.

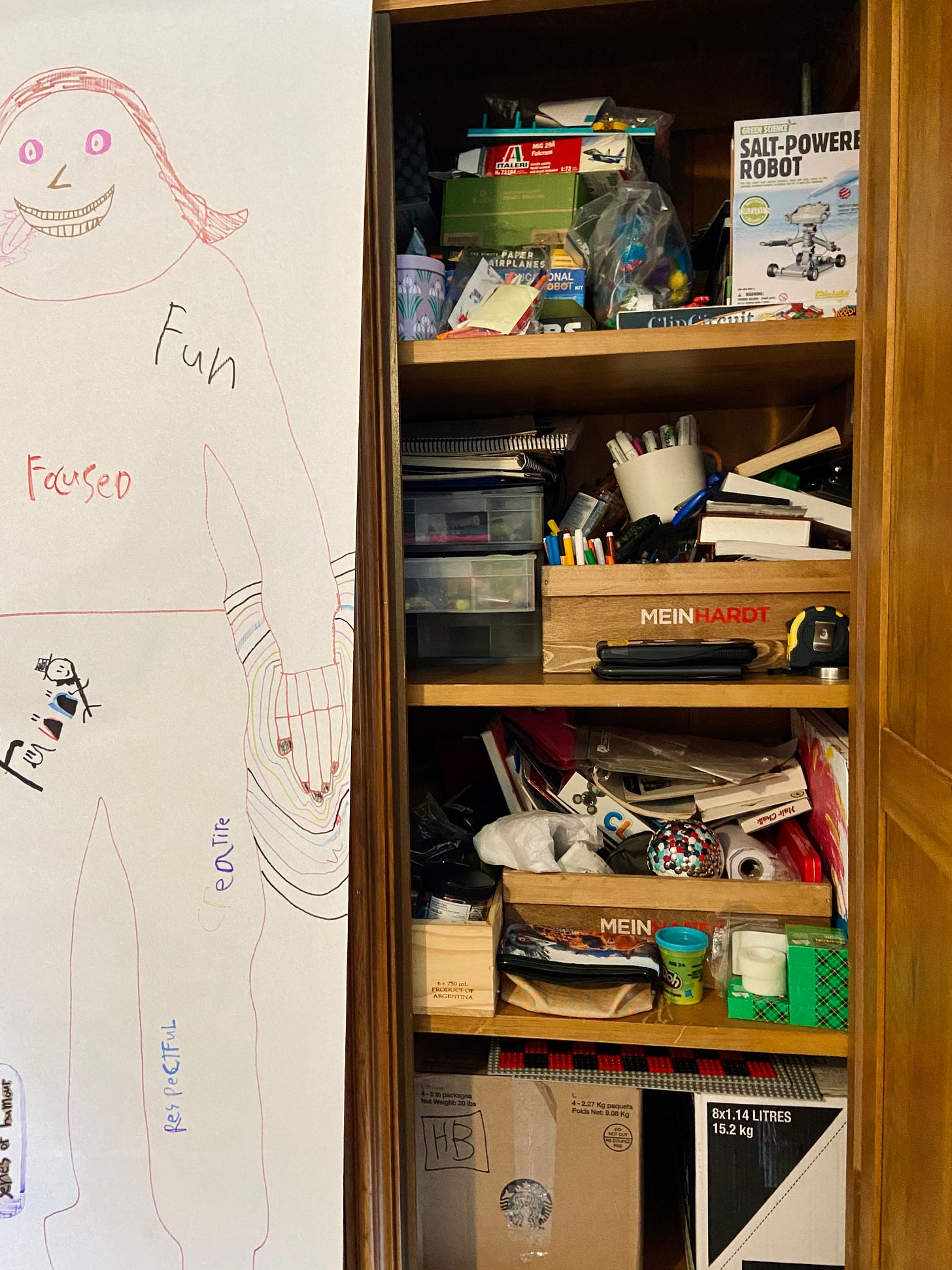

The family’s neighbors were already homeschooling, so together they made a bubble and did a year of “Hogwarts school.” The kids thrived.

Before the lockdown, Z had been having issues at public school too.

“He had a couple of friends there, but he was always being teased for things. Kids would make fun of the fact he brought food from home for lunch. They would tease him about the fact he has long hair and the things he was wearing. It's this whole culture of disrespect and teasing that's just normalized,” Allie says.

Homeschooling was much less stressful for Allie too, not having to shuttle three kids to three different schools anymore. “We wake up when we want, we decide what we're doing. Each day we eat lunch together as a family at home. We never wanted to push the family back into the school routine again.”

What about the curriculum? Were you concerned about what they were learning academically?

No. I have a couple of issues with school curricula. Having moved countries, curricula are completely different in different countries. The curriculum is set by the government, and from our perspective, it's completely arbitrary as to what they're going to learn when. Also, because I teach at university, particularly teaching first-years, they have a massive disparity in what they've learned based on the countries they grew up in and what they've been exposed to.

I feel schools are not preparing kids for life. Some of these first-years have no time management skills. Here I am looking at these kids who've graduated from school who can't cope with life. I think our students have such a huge amount of mental health problems. They're stressed. They're lacking in a lot of life skills.

What life skills do they not have?

Time management, self-control, self-regulation, and intrinsic motivation. I think school focuses on external motivators to get kids to work. I don't think it serves them any purpose in life. Because when they get to university, my role is not to monitor them and say, “I'll give you a good grade if you do your assignment.” They either hand it in or they don't. If they don't hand it in, they get zero. I think the school doesn't help them with that at all.

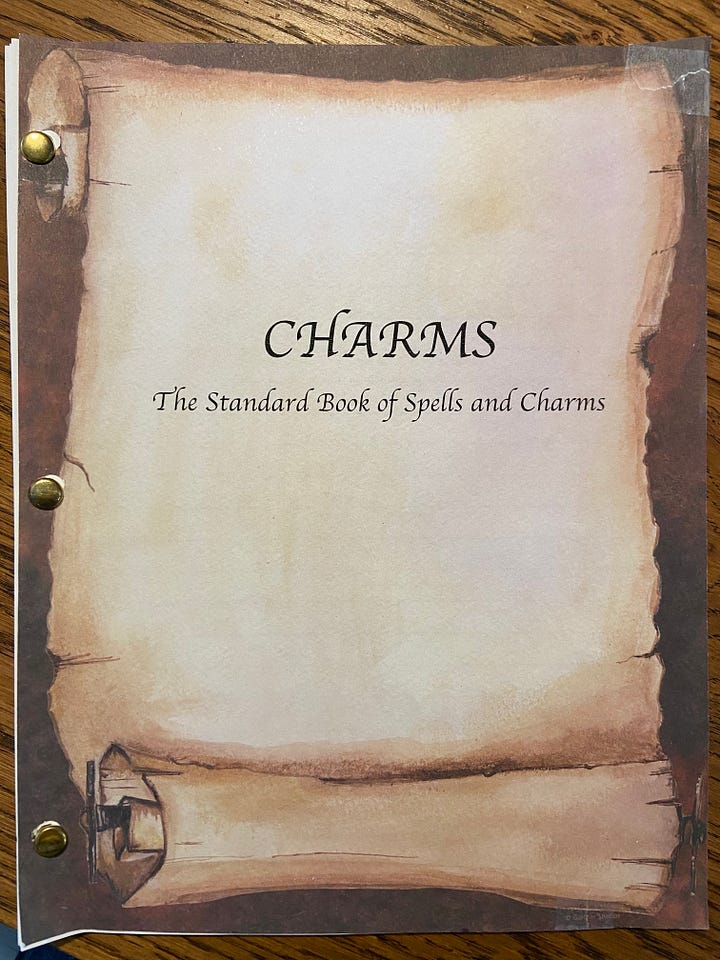

So we thought, well, if we focus our homeschool curriculum on life skills and mental wellbeing, social-emotional wellbeing…with the neighbors, we did a whole year of school at Hogwarts. Actually L got this out this morning, which was from the Charms class. [Allie shows me the workbook she put together, for learning cursive handwriting.]

That theme worked for everyone from H down to the little kids?

They loved it. Actually I think we all felt that was the best year of homeschool we had. It was fun and relevant to something they're really interested in.

Did you have to be very deliberate in the Hogwarts lessons and think about, “What do I want them all to be learning through this and how do I incorporate it?” Or did it organically just keep happening?

I'm definitely philosophically more in the unschool camp, where what they learn is less important than how they learn and having them know they can learn whatever they want to learn. Learning how to learn is what we've focused on more.

How did you teach your kids to learn how to learn?

I don't think we put much faith in kids. We think they need to be taught, but I don't think they do. We don't give them time actually. What we did instead is give them unlimited time for exploring and learning.

It's a much slower process that doesn't have as much output, so it's hard for a school to do that because schools are required to report. How can they report if they don't have evidence? So kids have to work to make evidence simply to justify what they're doing. Whereas with, say, Hogwarts it was like this buffet of opportunities to explore. We let them go really deep in ways they enjoyed.

What was the process of letting them just explore? How long did it take? How did they start exploring?

Among unschoolers, there's a big variety: some people allow their kids to do anything, and others ask things of their kids. I'm somewhere in the middle. We set up a family routine: rather than a schedule where it's more rigid, each evening I would lay out on the dining table a morning activity. They'd have breakfast doing the activity. Each day of the week, we had a theme for the day. If we had magical creatures on Monday, that would be the focus, so I'd put something on the table that would have something to do with a magical creature.

Then we would read together for an hour. I would read from some books, and they would do their hands-on activity while I'm reading. For example, for L, it would be a dot-to-dot, or a coloring-in or sewing.

It's always a hand-y kind of thing as you were reading to them?

Yeah, to keep their hands busy. We would do that for an hour and then my requirement was they had to do Arithmancy, which was math, but I called it Arithmancy and stuck a cover on the book so it looked like a Hogwarts book. They each had a little trunk, so we'd be like, “Get out your trunks and get out your Arithmancy.” And we did Charms, which is the cursive writing.

The day would focus on the theme. We used Brave Learner a lot for how we set things up. It's by a Canadian homeschool mom who has all these tips and tricks for how to set up your day and your home for learning.

My focus was to make sure they were doing math and writing. Everything else would come through our learning. They were done at about 11 o'clock every day.

Was it hard to get them to do the exercises?

It depended on the kid. L does not like writing, but because they were all doing it together and they knew once they're done at 11 o'clock, they're done. Then we would go do something with the family next door, go to the forest. We would do craft activities and things like dissecting owl pellets and baking.

[Here Z comes in to get some snacks. He, H, and two friends are taking a science class with a freelance science teacher who comes to their house.]

There are probably a lot of resources for homeschoolers like the freelance science teacher, right?

Yes. Last year, we organized medieval swordplay classes; there are people who teach the most amazing things. The kids think they're just learning swordplay. But the teacher would be constantly talking about medieval history.

The boys go rock-climbing one day a week with other homeschooled kids. There's often pool meetups or park meetups or special events, like they did an avalanche training course.

The comments we get about our boys is that they're really happy to be themselves and look different and be different. They talk to adults in a way that others don't. Z doesn't wanna become like all the other high school kids where they have to become brutal to protect themselves. If you're not dishing out negative comments, you're going to be receiving negative comments. I feel like that's the choice high school kids have.

But do you think that with the difficult situations at school, they're also learning things–dealing with people and people not always being like them or liking them?

It is a really interesting question. I think we push kids too young to try to cope on their own with social issues. So yes, I do think my kids will be delayed in being put in those situations, but I think they'll be more prepared for dealing with them. They also have exposure to much more diversity. Although at school they're exposed to diversity, I don't think they're exposed to how to be inclusive of diversity very well because it's too big.

There's so much the teachers don't notice. So much happens actually on purpose away from teachers. So the difference is, [at home] they're exposed to inclusion and support a lot more. They're mentored a lot more by the greater community, there's more adult presence; the homeschool families tend to be much more parentally involved.

But I do wonder what is the better learning–is it learning to cope with being bullied every day? Or is it learning that I don't have to keep going every day?

There could be a downside to being forced to keep going to school–in a work situation, if they're being bullied by a boss, do they just keep putting up with it?

Do you feel that in homeschooling or unschooling they're not getting anything in terms of academics that they would be getting in school?

Sure, they're not getting some academics, but I don't think it's as important. It is something that I waver on: should we push them more or should we let them explore more?

I'm the product of a school system and I won't put my kids through that. I feel like I lack in self-awareness, self-knowledge, self-confidence in knowing who I am, knowing what I want. I learned how to do what people expect me to do.

I feel so happy for our kids having a real childhood. When I was Grade Five I was doing two to three hours of homework a night. I'd be at school all day. I'd work all night. I didn't complain about it because that's what I was told to do and my parents thought there was no other way.

What do you feel like you lacked in that rigorous traditional schooling system?

I think we lacked time to explore and make choices for ourselves. Like figuring out what hobbies do I actually like? As an adult it’s like, what do I like to do? I don't even know. Having real time and time to get bored. We try not to over-schedule or over-tell our kids to do things cuz that’s when they're bored and creative.

I think the future needs creative thinkers. We are hoping to foster that in them, so they learn how to self-entertain.

We're also very anti-screens. They get half an hour a week to play video games. We have the Nintendo DS, because it's social, there’s no first-person perspective, and it's pixelated graphics. We chose that specifically. They asked a few years ago if they could play video games, and we did a lot of research into which would be the least addictive.

We see kids who cannot get off their devices. Even while they're playing Dungeons and Dragons, one of their friends is on the screen the whole time. The other thing I read years ago was that the reason screens can be so addictive is that for teens especially, real life is so tedious. School is so boring, and they revert to screens to be entertained.

This research was saying that to avoid that, parents need to put in a lot of time and effort to fostering their teens’ hobbies, so we purposely make sure we help them get involved in hobbies.

For instance, we got our eldest into farming when he was 10 and he still volunteers at a farm once a week. He does a lot of heavy work and he does planting and harvesting and weeding. Z has creative hobbies; he makes jewelry and sells it.

Besides the video games being addictive, are there other reasons why you limit screens so much?

We saw with Z particularly that screens alter his behavior a lot. Time on a screen would be followed by difficult behavior.

What was he doing on the screens?

We tried Minecraft.

Oh really? We haven't done it much, but that's supposed to be a productive thing.

It's a really interesting debate of should we allow kids on screens if it's educational. There'll be people that say “That's a good thing because they're learning a lot of creative skills.” And there's others that would say, “But they could learn all those creative skills doing something off screen.”

The screen is like this vortex that sucks them in, and they stop doing other things. When Z did the term at school, he was required to bring a device for school; he was on it all day and he stopped making jewelry completely.

That's where you can see it—it's so obvious when you've tried things from another camp. We can see so clearly the change in him. When we tried Minecraft with the boys when they were younger, H said he couldn't stop thinking about it. It's so consuming. Recently, Z asked if he could start playing again. H did it once with him, and straight away was like, “I can't stop thinking about it. I just can't do this.” He recognized that.

Did you find any resistance to taking away their screens?

No. We had a family meeting and talked about all the things we've just said. I talked to them about the research paper. We asked them, “What does it feel like when you’re playing them? What does it feel like after you’re playing them?”

We invited them to share what they think: should we have limits? Should we stop altogether? We agreed that we would foster their hobbies, that this would be a trade-off. We would go out of our way to encourage their hobbies.

We’ve been told by teachers that we are really extreme. Z's teacher wanted them to do IXL math homework, and we said no because he doesn't do it on the screen. If she wants them to practice math, we can practice math.

Why do we have to gamify everything? Because then what happens is if something isn't gamified, kids don't wanna do it. They're so used to having everything being a fun game, but again, there's no intrinsic motivation.

Do you feel as a professor there are things that you are doing with your kids at home that you're bringing into the classroom, or vice-versa?

I must be bringing it in because students tell me that I'm very different. The courses I teach are really different to others. I do a lot more real world experiential learning and I bring in guests to talk, and I value process and progress over the output.

Also, I did my postdoc in the education faculty with a prof whose work is all about real world experiential transformative learning. I learned a lot there.

Your postdoc was in education?

Yes, but all in sustainability. My PhD was architecture and sustainability, my postdoc was education for sustainability–how we teach students to become sustainability leaders is to immerse them in the real world.

The more connected they are to the real world, the more they'll take leadership. That must also be why I'm really anti-screens. Because they're just not the real world. So if there's a real world alternative, then we always choose it in our homeschool.

But it's also always evolving and changing. I can say right now this is what we're doing, but it doesn't mean that we'll keep doing it.

Is there anything that you would've changed on this educational journey with your kids?

I would've done this from the beginning. I feel really sorry for H. I think we pushed and pushed for him to fit into schools and it was a really negative experience.

He went to a school in kindergarten all day, came home, had to sit at the table and do homework. He was five. He had to do spelling tests. I've apologized to him so many times.

We did send L to public school for kindergarten and beginning of Grade One. But I told the teachers, we don't do homework. She won't do spelling tests. We won't do any of these things. The teachers were amazing. They supported our choice. They would keep telling me, “Just so you know, she's behind grade level,” but they were really supportive.

Did it make you anxious to hear that?

No, because they were supportive. She had these two amazing teachers who could see that this isn't really necessary. There's a lot of teachers who agree, but their hands are tied.

We didn't actively teach her to read. I had moments where I was like, “Ooh, is this the right thing?” She learned when she was nine and by the time she learned it was a very slow process. But once she learned, she could read novels. It's like this moment of, “hey, I've cracked it.” Now she reads nonstop.

Research shows that for a child growing up in a literary household, who doesn't have a learning difference that would stop them learning to read, they’ll naturally learn to read if we give them time.

I had a friend tell me that their little girl who's six years old is going to have to repeat Grade One. “We are drilling every single day because she's not learning to read. So we do phonics in the bath.” I had this vision of this little six-year-old struggling to learn to read.

What's she internalizing? She's internalizing “there's something wrong with me. I'm going to have to repeat Grade One because I can't read.” I worry about the damage all that internalizing has done.

It seems like the social aspects for homeschooling have not been a problem, right? Because you've had communities?

Socializing is different for homeschoolers; they socialize much more mixed ages. That's actually a more natural social setting for humans, to be in mixed ages. They socialize with elders in the community and we try to find the mentor-type people, and they socialize with mixed aged kids.

There's a lot more gender fluidity in terms of social groups in the homeschool community as well. We find school groups are very gendered. The girls play with the girls, we found even at forest school. We find in the homeschool community, it's just not a thing. It doesn't even come up. And then there's a lot more opportunity for them to mentor younger kids because they're around younger kids, whereas at school they're typically not.

That's good for them as well. Z said once he has far more social time now because with school, it's this myth that they're socializing all day. They're dealing with social issues all day, but the chance to free socialize is really limited to lunchtime.

That's true. It's a very regimented situation.

Every now and then I'll wonder, what are they missing out on? There's definitely things that they are missing out on and I have to weigh it up versus the damaging effects of school.

We always end up going, well, I think the pros outweigh the cons. Every year we reassess. There's no perfect situation.

Pretty Good Things

Here are two resources Allie recommends:

Brave Learner

Allie set up her homeschool according to the Brave Learner book, following suggestions such as always having an art table open for children to create. She also used the Brave Writer method to teach her kids to write. Author Julie Bogart states, “The core difference between Brave Writer and other programs is that we teach writing much the way professional writers teach writing…Professional writing instruction usually starts with a person—what do you have to say?”

I agree with this approach! If a child learns to love reading and writing, I don’t believe there’s any need to learn how to diagram a sentence. All the writing skills will come naturally, with practice.

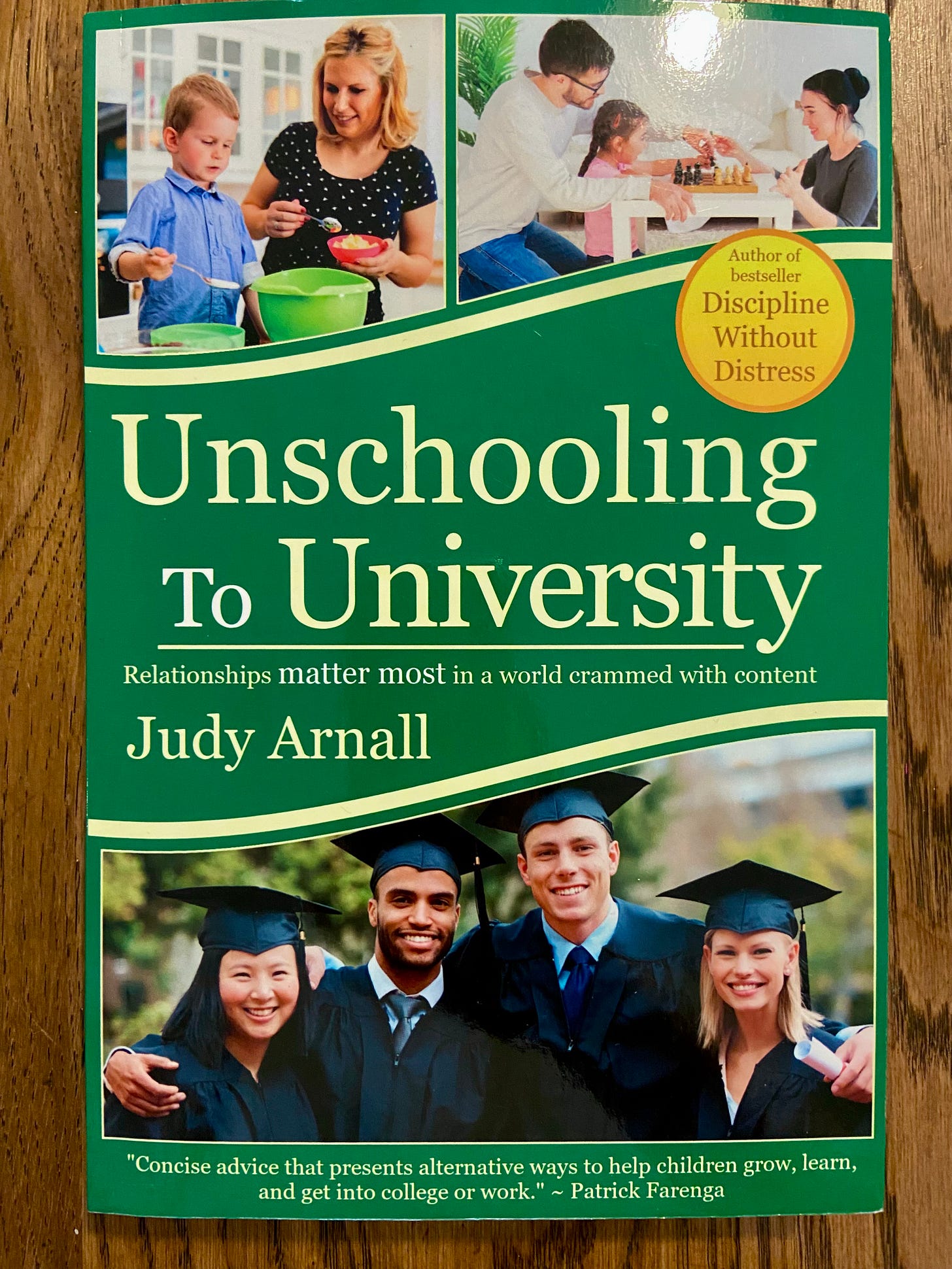

Unschooling to University

Unschooling to University follows the paths of 30 Canadian kids who were unschooled for all or part of their childhoods, and later went on to university. Allie lent me her copy and I am intrigued. I’ll report back after I read this book.

Unschooling integrates learning with context

Compartmentalized subject learning is disconnected learning. Classroom time is tight. So many subject outcomes are packed into the curriculum that learning must be carefully divided into scope and sequence…Unschooling doesn’t compartmentalize subject areas. All core subjects are related to everything else. In unschooling, a child can delve into a topic as deeply he wishes.

—Unschooling to University