Schools of nature

In which we visit a forest school and an alpaca farm

Beanie has now finished her first two weeks of summer camp at Red-tailed Hawk Forest School, the same school she attended during the 2020-21 school year. She’s completing the seasonal cycle, having already seen the school in fall, winter, and spring. It feels right to close the loop.

As someone who never grew up with real seasons, I’m constantly amazed by how different the landscape looks from month to month. When I came back for the summer and walked the trails, it wasn’t just that they weren’t buried in snow, but that vegetation 6, 7, 8 feet high lined the sides thickly and impenetrably, as if it had been growing for years.

(..I thought for a moment of not including what I just wrote, about my astonishment, because many of you have lived through seasonal changes, so what’s the big deal? Then I realized: the kind of landscape change I’m talking about wouldn’t necessarily be obvious if you live in a city or suburb. To see it, you’d have to be around plants that grow wild, and that doesn’t always happen in suburban yards or city parks. Even if we are surrounded by trees and flowers, we aren’t necessarily in natural surroundings.)

Many years ago, when I worked at Cal EPA, I learned that the average American spends 90% of their time indoors. Does that surprise you? It surprised me, and that number stuck with me all this time. I would’ve guessed the percentage would be high, but not that high. We must lose something when we are inside almost all our lives, walking around on manmade floors within manmade walls, often with windows shutting out any birdsong or outside air.

Beanie is so lucky to have these opportunities to play outdoors all day. At forest camp, the children spend time playing in the woods, then have a swim lesson in the pool, lunch and art back in the woods, a walk down to the creek where they catch crayfish and minnows (and then release them), sing songs, play games, and run weaving their way around the trees.

During the school year, they’re taught to poke at mushrooms or move logs with sticks, not their fingers. They learn to recognize plants because they encounter them every day. In fall and spring, they get very muddy—I did laundry almost daily during those months, and ran through a couple of bottles of stain remover.

They stay outside all day every day, through the winter, except when the weather is really terrible. They don’t mind it at all—Beanie didn’t complain once about being cold or wet.

They spend whole mornings making snow carpet rolls.

One of the first lessons Beanie learned at forest school was the salmon life cycle. The school has a creek that runs through its grounds—Silver Creek—and in September, soon after fall semester begins, is when salmon swim upstream through Silver Creek. The kids would hike to the creek every morning and observe what the salmon were doing. This way, Beanie learned about the egg, fry, and alevin stages because she saw each with her own eyes. At the end of the cycle, her teachers brought them to see the salmon that had died after spawning. I was glad; that seemed like an important part of the cycle to understand, another loop to close, that is as vital and inevitable as eggs, or fry, or the seasons.

Who knew alpacas sweated so much?

Their fiber is seven times warmer than sheeps’ wool, so it’s no wonder that when they get up off the floor in the summer, they leave alpaca-sized sweat puddles.

These are the kinds of things you glean from visiting an alpaca farm like the one we went to this Sunday. It was a sunny day meant for toodling around the countryside, splashing around a waterfall, picking up a carton of eggs from someone’s yard, and visiting an apple farm and some alpacas—so we did it all. A lovely, not too hot day, perfect for spending outdoors and breathing fresh air.

Carolyn Lilleyman, who owns the Kickin’ Back Alpaca Ranch with her husband Doug, spent a good 90 minutes with us, patiently answering our questions. I’m now armed with a whole bunch of alpaca facts: did you know their fiber is hypoallergenic? The fiber doesn’t smell either, unlike other animals’, because it’s not greasy or oily. Alpacas are naturally “potty-trained” and will all go to the bathroom in one communal space, making it easy to clean after them and keep their living space “fragrance”-free. Honestly, they seem simpler to care for than dogs. They’re also gentle and friendly. If we ever have a large plot of land, I would be inclined to keep an alpaca or two (actually, definitely more than one and probably more than two—I also learned that alpacas are herd animals and the bigger their herd, the happier they are).

We fed and petted the alpacas on their necks—so soft!—as they don’t like being touched on their heads. The babies are called cria, and they are adorable, curious, and unafraid of strangers. They like to get close and nuzzle.

We left with a lot of alpaca knowledge and love, and a small stuffed alpaca made from real alpaca fiber, which Beanie named Tiny Treasure in honor of one of our new alpaca friends.

I didn’t grow up interacting with woods and creeks and lakes the way Beanie does; certainly nothing comparable to the hours and hours of freeplay she gets to have. Studies show that she should be getting physical, psychological and perhaps even cognitive benefits from being in nature. I don’t know exactly how Beanie’s brain might be getting sharper through forest play, but there’s an area of research that has grown around asking that question.

Attention Restoration Theory posits that spending time in nature restores the ability to concentrate, especially on tasks that require a high degree of attention, such as the Backwards Digit Span test. The theory was first put forth in the 1990s and is still a nascent area of inquiry. As far as I can tell, studies have so far been small and the science inconclusive, which makes sense with the differing study designs and outcome measurements—and even different definitions of “nature.” Time (and more research) will tell if nature actually improves cognitive function.

I’ll tell you what, though. Whether or not nature improves focus, it does something in my brain. Like a brain massage, gently pressing me to let go of tension and clear out the fog. When I take walks, I usually listen to podcasts, but when I get to the trail, I take out my earbuds and listen to the birds and the rustling leaves for a few minutes. If I’m thinking through a problem, this is often when the answers come.

So I believe it, that nature is powerful: the hikes on forest school grounds, the games in the woods, those hours spent hunting for crayfish and minnows at Silver Creek—they’re helping create better little people in more ways than one.

Pretty Good Things

“Ox-oh,” not “oh-ex-oh”

Chances are, you have some OXO in your kitchen. I do too. You just can’t get a better peeler for the price, IMHO. If you want to learn more about OXO, how they came to be, and their design philosophy, this will be a good read for you.

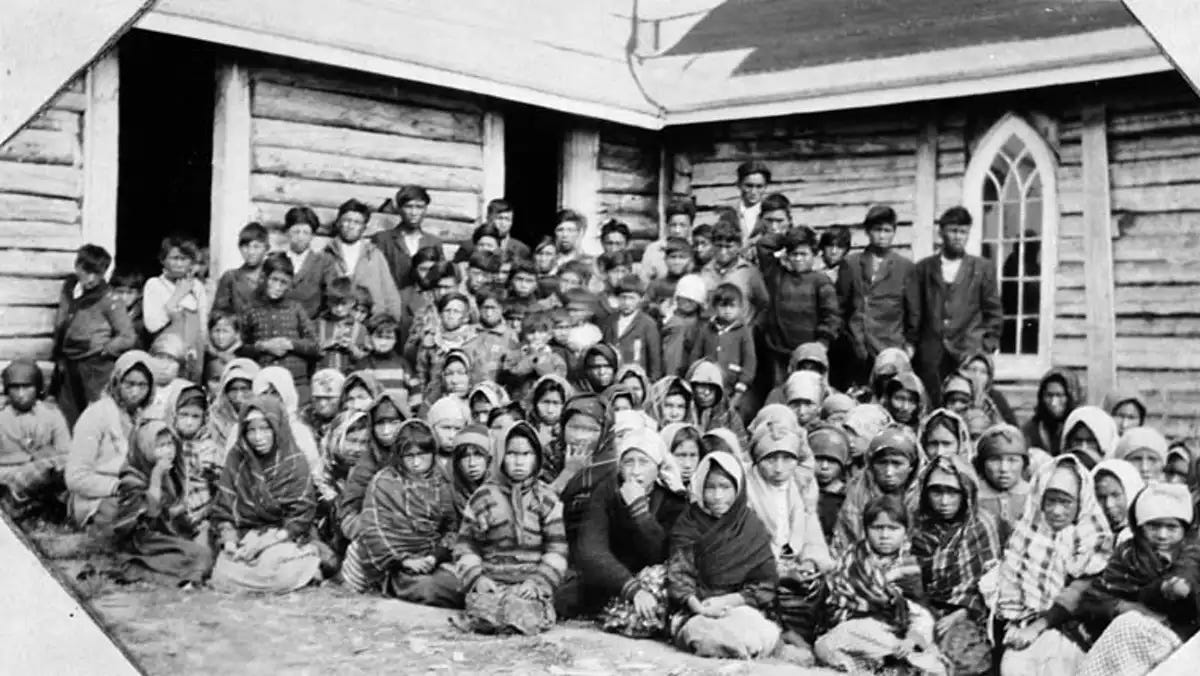

Indian Day Schools

The atrocities committed at Indian residential schools in Canada got media attention and belated Canadian government acknowledgment with the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. Some 150,000 Indigenous children from the late 1800s all the way to 1997 were forcibly taken from their families and sent to board at schools where they were isolated from their culture, made to speak English or French, practice Christianity, and regularly abused.

Lesser known are the Indian Day Schools, almost 700 of them, that 200,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend over more than a century. As with residential schools, day schools have a tragic history of death and abuse. This The Conversation piece links to many other stories and news articles that detail the horrors suffered.

The new system of Indian education, overseen by the Department of Indian Affairs, had two distinct prongs: day schools, which were often located on reserves where children could return home at the end of the day, and boarding or “residential” schools, where children resided at schools far away from their communities — sometimes children attended both, at different times, during their school years.

The two kinds of schools shared the same goal: to solve the so-called “Indian problem” by undercutting and delegitimizing Indigenous ways of life to better facilitate settler capitalism and Canadian nation-building.

How to Show Up For Your Friends Without Kids — and How to Show Up For Kids and Their Parents

A good reminder, with some specific guidance on how we can be more of a community to one another.